You Can Trick Your Customers, But Is the Trick Really on You?

Plus: The 'Aaron's staff technique' and affirmation that alliteration is awesome

We’re getting close to the end of the month, so it feels like an appropriate time to ask: Trick or treat?

For marketers, the answer is definitely the former. We love tricks. Tricks to get people’s attention. Tricks to convert prospects into buyers. Tricks to get buyers to buy more.

On that last topic, the latest edition of Kevin King’s always-valuable Billion Dollar Sellers Newsletter (BDSN) shares a little Old Gold trickery that will be very familiar and attractive to DR marketers.

That said, I have some doubts about it. Let’s dive in.

Old Gold🪙

The trick in question comes from Dan Ariely’s 2009 book, Predictably Irrational.

Ariely’s book opens with a story. One day, while “browsing the World Wide Web” (this is 2009, after all), he came across an ad for the magazine The Economist that offered three subscription options:

An online subscription for $59

A print subscription for $125

A print and online subscription for $125

Ariely writes:

Who would want to buy the print option alone, I wondered, when both the Internet and the print subscriptions were offered for the same price? Now, the print-only option may have been a typographical error, but I suspect that the clever people at The Economist’s London offices…were manipulating me. I am pretty certain that they wanted me to skip the Internet-only option (which they assumed would be my choice, since I was reading the advertisement on the Web) and jump to the more expensive option: Internet and print…

[T]he Economist’s marketing wizards … knew something important about human behavior: humans rarely choose things in absolute terms. We don’t have an internal value meter that tells us how much things are worth. Rather, we focus on the relative advantage of one thing over another, and estimate value accordingly.

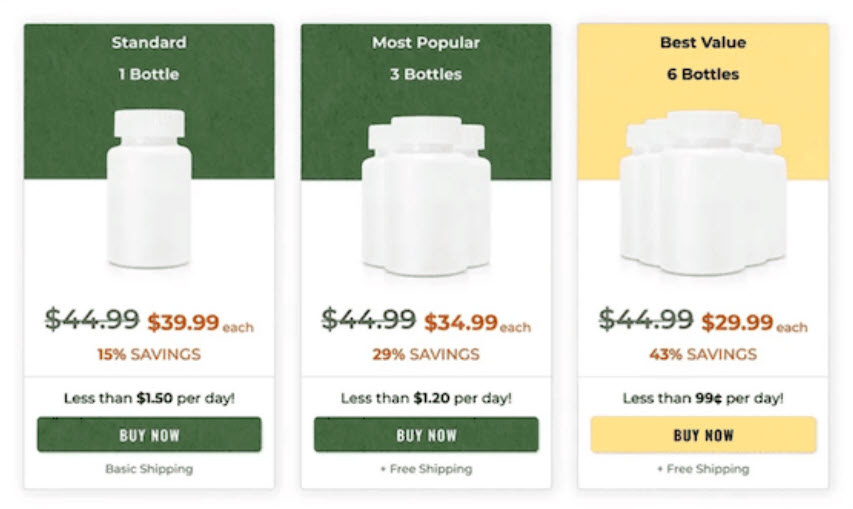

Ariely dubbed this technique “decoy” pricing. King shares a more recent example from Harry Molyneux of DTC Pages, a company that specializes in optimizing conversion rates for Shopify websites. In a recent test, they found that this offer presentation performed best:

The “eye-catching color” of the six-bottle offer combined with the larger comparison prices and the “price per day” calculation pushed consumers toward the higher-revenue option, King explains. Doing the math, it helps turn a $39.99 sale into a $179.94 sale. Cha-ching! Great trick, right? Ready to run out and implement it?

Well, not so fast. I’m not sure if he meant to draw any connection, but King also included an interesting statistic in the same newsletter:

The return rate in 2023 was about 15% of total U.S. retail sales….

The average online return rate is 18%, or $247 billion.

This juxtaposition made me wonder: Are marketing tricks like “decoy” pricing really worth it? Or are we just tricking ourselves?

I used to do card magic when I was a teenager, and one of the key things you learn is how to direct people toward the outcome you want. It’s called a “force.” They think they are picking a card of their own free will, but you are subtly forcing them toward the card you’ve made the centerpiece of your performance.

The examples above are the marketing version of a force.

The trouble is you also need to consider the final moment of the trick. With magic, people are left holding a surprise card and feeling delighted about it. With marketing, they are left holding a surprise receipt and feeling … not so delighted. Magicians never reveal the truth of a trick, but receipts always reveal the truth of a marketer’s trick, which is often a large amount of money the customer did not intend to spend.

That’s why I suspect there is a correlation between this kind of marketing trickery and the high return rates King shared. The problem with online sales, especially, is that there’s an 800-lb gorilla in the market called Amazon that is setting everyone’s expectations — and those expectations include free returns for any reason, at your expense.

So I ask again: Who are we really tricking? Worst case, you’re paying for shipping twice and incurring the other costs of returns. Best case, you’re a net/net winner because enough people were too lazy to return the five extra bottles in that “Best Value” package they didn’t want. But then what are you doing to your brand when those people inevitably feel manipulated?

I’m not saying these tricks are all bad. I’m only saying marketers should be careful how they use them. Ariely saw that Economist ad as a way to get him to pay for a print subscription he didn’t want. However, he might also have viewed it as getting a free online subscription for the same price as a print-only subscription. It depends on the perspective. On the other hand, Molyneux’s offer is harder to see in a positive light. I doubt many costumers who came in willing to buy one bottle for X will feel good about ending up with six bottles for nearly 5X.

The DR marketing experts at BulbHead have chosen to split the difference here and use what I will call a “soft force.” Here’s an example from the website for Hempvana pain relief cream:

Notice they use the same “eye-catching color,” best-value language (“most popular”) and itemized pricing (“$X/ea”) of the Molyneux decoy-pricing arrangement. However, the default/highlighted offer isn’t the revenue-maximizing “4 pack” (i.e. more product than the customer probably wants) or even the “Subscribe & save” (which can lead to the customer accumulating more than he/she probably wants), but rather a 2-pack that saves the customer a little money while also nearly doubling the order value.

It’s about as close to a win-win as possible. As a marketer who likes tricks just as much as the next guy, I have to say: I like it!

Chart Watch👁️

Everglow

Pitch: “Never lets the hard-water chemicals or chlorine touch your skin”

Offer: $29.99 for one with free shipping, 2nd one for 50% off

Marketer: Emson

This first tested in Q1 at a time when Interlink’s AquaCare (No. 6 on the 2023 True Top 50) was still on the DRMetrix weekly charts. Now AquaCare is off the charts, and this campaign has popped up in the Top 10.

Back in 2013, I identified something I called the “Ouroboros strategy.” This was my way of explaining how two similar items could be hits back to back, one year after the other. It was unusual in an industry where marketers often waited a decade to bring back their hit products, but sometimes it happened, and it worked. My theory was that, like the mythical snake eating its own tail, marketers were cannibalizing the ‘tail’ of their sales from the previous hit.

This example doesn’t quite fit, though, since it’s someone else eating the tail. I guess I need a new metaphor. How about the “Aaron’s staff technique”?

Note: Some of the links in this newsletter go to The Library of DRTV, my subscriber-only archive of DRTV projects going back to 2007. Want in? Just scroll down and support my work by upgrading to paid. It’s $5.99 per month or $59 for the year. As a special thank-you, I’ll send you a surprise gift easily worth more than the cost of your subscription.😉

Fun Fact🧠

Thomas McKinlay may have changed the name of his publication to Science Says, but he hasn’t changed the level of quality he delivers each week. His newsletter is still the best source of research-backed marketing knowledge I have ever seen. Today’s fun fact is another McKinlay treasure:

Starting with a strong consonant (such as p, t, b), using wordplays, and alliterations

makes brand and product names more memorable.

The best DR marketers I know are masters of wordplay. I am also acknowledged for my affinity for alliteration (see what I did there?). So it’s great to have scientific support for something I have known in my gut for years.

It’s one of those things that can be hard to defend. You just know that product name will sell better because it ‘sounds’ better, but you can’t always run an A/B test to prove it. Well, now you can cite “an analysis of TV ads from 480 national brands,” which found consumers were more likely to recall brand names that:

Start with a strong consonant that involves suddenly closing and then opening one’s mouth (k, g, b, p, t, and d)

Include an alliteration (e.g. Coca-Cola or Pepsi)

Use puns or wordplay (e.g. Arrid deodorant, a wordplay on “arid” meaning dry, Durex condoms highlighting their durability, or Sunsilk shampoo playing on silky hair)

Fit with a product’s identity (e.g. WD-40 for a chemical-based product or Clean and Clear face wash)

Had an unusual spelling (e.g. Kool-Aid)

The Journal of Advertising article that revealed the above is here, and the Science Says newsletter reporting on the study is here.