Don't Even Bother With Products That Can't Live Up to the Hype

We're at the last, and perhaps most important, of my Divine Seven criteria

At the beginning of this year, I shared “the first product checklist I ever created, promoted and taught to clients” — the Divine Seven (D7). Since then, we’ve been on a journey together as I explore how each of the criteria hold up today. (Click here or scroll to the bottom for the complete list.)

As we consider the seventh and final criteria — CREDIBILITY — I invite you to time travel with me…

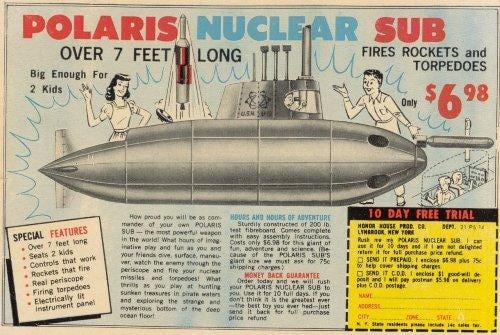

It’s the 1960s. There are three television networks. Most people read newspapers and magazines. People shop at department stores. Direct marketing takes place via direct mail and catalogs such as Sears Roebuck & Co. Young people often buy toys, novelties and hobby supplies from ads in the back of their favorite comic books and magazines. Here’s an example of such an ad:

Someone named “Mister Nizz” has made a fun video of what he imagined when he read this ad.

Mr. Nizz writes:

I can’t tell you how much the 9 or 10 year old me wanted it to be true, yet at the same time, I KNEW it was going to be a toy, and made cheaply at that. Hope perversely endures. In the back my mind I thought that, hey, maybe, just maybe it was a big plastic thing, with spring loaded torpedoes, large enough to house me and all my buddies.. maybe it will float, at least.. and hey, maybe we could take it to the pool an submerge it! This actually might be almost worth it!!! YEAH!!!

Having been duped before by the comic-book ads, young Nizz never pulled the trigger on that particular purchase. Good thing, too, because this is what that “submarine” actually looked like.

“Even in my my most optimistic moments, the smart part of me knew that these adults were taking advantage of me, of course.” - Mr. Nizz

Let’s get back in the DeLorean…

It’s the 1990s. Cable television has introduced many more television networks. People shop at malls and big-box retailers such as Walmart. Direct marketing still takes place via direct mail and catalogs, but now infomercials are a dominant force. Here’s an example:

A balding guy named Roy Rivenburg tried the product in 1995 — or, rather, the product was tried on him during a promotional stunt at an LA radio station. Here’s an excerpt from his first-person account in the LA Times:

By the time Ron finished aerosoling my cranium, I’d nearly asphyxiated from the fumes and a nervous panel of scientists had convened in Washington to investigate “a sudden and inexplicable” depletion of the ozone layer.

Was it worth it?

“You look 50 times better,” the deejays assured me. “Just don’t try to smoke a cigarette.”

…But after I returned to the newsroom, the reaction wasn’t as enthusiastic. A colleague who inspected the top of my skull said it reminded her of those old G.I. Joe dolls with the fuzzy hair.

And an editor diplomatically announced: “Your head is the funniest thing I’ve seen in years.”

I think you get the point.

When I put together my criteria for DRTV products, I was fully aware of stories like the ones above — and many more. Indeed, when I told people what I did and mentioned any of my hit products, the #1 question they asked was: “Does it work?”

They also mistakenly thought ‘As Seen on TV’ was a brand owned by a single company, which might have been a good thing if that brand did not stand for cheap products that never live up to the hype.

Is it any wonder, then, that I made my seventh criteria for products CREDIBILITY? You can almost hear me pleading in my original explanation:

People must believe it works as advertised. Many DRTV items that meet the previous six criteria fail here because the promise they make just isn’t believable.

Here’s an example I used in presentations at the time to illustrate my point:

The product on the left is a failed DRTV test. The claim was “instantly volumize your hair and add inches of height.” The product on the right (Bumpits) made essentially the same claim and was a top 50 success.

Back then, I argued the difference between success and failure was the credibility of the product. I explained that no one believed a comb alone could accomplish what was being promised. Bumpits, on the other hand, actually added ‘infrastructure’ to give women the high ‘Jersey’ hair they apparently desired at the time. (Is it a coincidence that Jersey Shore became a hit around the same time?)

This is where things get really interesting. Although that was what I argued, I had trouble believing it. (That’s right, my claims about credibility didn’t seem credible to me.) The reason? I had seen too many BS products succeed.

That’s the flip side of the examples above. I have no doubt hundreds of kids bought those stupid cardboard submarines because they were still selling when I was a kid more than a decade later. People sure did make fun of “hair in a can,” but thousands of men also bought it and tried it.

The problem: There was too much of a delay between product purchases and customer reviews. The most common methods of customer feedback then were testimonials (controlled and curated by the advertiser) and those random network news segments where reporters put infomercial products “to the test.” Otherwise, people had to wait for word of mouth to reach them. A low-satisfaction item might also have high returns at retail and quickly leave the shelf, but most DRTV products were short-lived anyway, so selling millions and then leaving stores before bad reviews could catch up was practically built into the business model.

As a result of all this, I ended up thinking I was wrong to have included CREDIBILITY in my criteria. I even dropped it from subsequent checklists … which brings us to today.

It’s the 2020s. The number of television networks is irrelevant. Newspapers and magazines are irrelevant. People mostly watch and shop online. Most direct marketing takes place online. Everything is nearly instantaneous and, importantly, there is no way to hide that a product doesn’t live up to the hype. If Mr. Nizz’s grandkid sees an ad for a nuclear submarine, he can find out in seconds that it’s really a carboard craft project. If Roy Rivenburg Jr. sees an ad for “hair in a can” (yes, it still exists), he can find out in seconds if it’s worth trying and what he should expect.

In fact, in some ways we have moved past credibility as a product criterion. Unlike the days when I taught the D7, I don’t have to guess whether people will look at my products and believe they will work as advertised. That’s because I can use instantaneous online methods (e.g. surveys) to ask real people and find out.

No, what I have to worry about now is whether consumers will say my products live up to the hype after they buy them. The roles are reversed. They have all the power. They might even be completely unreasonable, having had absurdly high expectations even after I was careful to lower them.

If I fail, I won’t have the luxury of selling millions before sales tank. I’ll quickly get killed in the online ratings and reviews, and the joke will be on me.

The Divine Seven

1. UNIQUE

(Article: Build the Marketing Into Your Product to Maximize Sales)

2. MASS MARKET

(Article: These 3 Powerful Letters Can Greatly Improve Your Odds of Choosing Hit Products)

3. PROBLEM SOLVING

(Article: The Problem Scale Can Guide You Toward the ‘Heart Attack’ You Seek)

4. PRICED RIGHT

(Article: What a Huge Walmart Mistake Can Teach Us About Product Pricing)

5. EASILY EXPLAINED

(Article: Never Try to Sell a ‘Swiss Army Knife’)

6. AGE APPROPRIATE

(Article: Why TikTok Advertisers Shouldn’t Sell Canes)

7. CREDIBLE

(Article: Don’t Even Bother With Products That Can’t Live Up to the Hype)

Quoteworthy📝

I came across two quotes this week that are worth sharing, both from the same book.

“The difference between baseball and business...is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution. When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four.

“In business, every once in a while, when you step up to the plate, you can score 1,000 runs. This long-tailed distribution of returns is why it’s important to be bold. Big winners pay for so many experiments.” - Jeff Bezos, 2015 letter to shareholders

As I shared on X recently, that last sentence struck me as the perfect encapsulation of the DR business model. Next quote:

“Make people an offer so good they would feel stupid saying no.” - Travis Jones

This was the point of my article, “What a Huge Walmart Mistake Can Teach Us About Product Pricing.” It echoes what the lady in that article said about buying three TVs from an erroneous Black Friday offer: “I didn’t even intend to buy a TV … I bought a TV because I was like, ‘I'm stupid if I don’t.’”

The source of the above quotes is Alex Hormozi’s $100M Offers. (He liked that second quote so much, he made it the subtitle of his book.)

News(letters) You Can Use📰

A recent edition of Why We Buy, an excellent newsletter about buyer psychology, is all about a topic that will be familiar to readers of this newsletter: cognitive load theory.

Author Katelyn Bourgoin goes deeper into the topic than I did in my article, “Never Try to Sell a 'Swiss Army Knife’.” She also gives three pieces of practical advice that sellers can apply immediately:

‘Chunk’ similar sets of information together like LEGO does to streamline navigation of its online catalog.

Simplify complex topics like WeightWatchers did with its points system for dieting.

Accompany technical specifications with simple images, such as icons, like GoPro does on its website.

For screenshots and further details, check out the full newsletter. To sign up for future editions of her newsletter, you can click here.